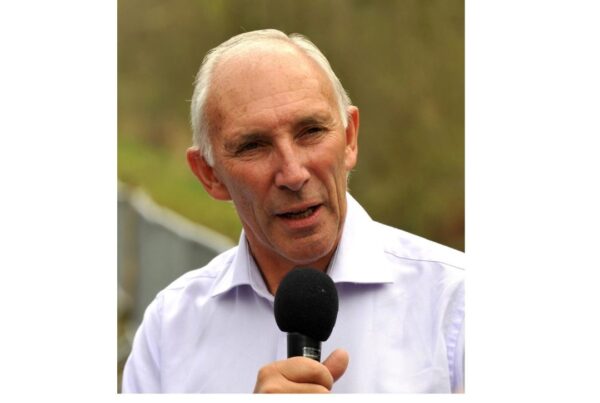

Graham Watson is a world renown cycling photographer. Over his career, which has spanned four decades, he has been at the centre of innovations within the sport, such as the pioneering of photography from the back of motorcycle. As cycling changed, so did the camera and the techniques that Graham employed. As a consequence, the entire art of cycling photography evolved. Now retired from chasing the peloton down the side of mountains at 100kmph, Graham has had time to reflect on how cycling photography has changed.

Evolution of colour photography

The early days is almost unimaginable. Originally, Graham used to shoot photographs using black and white film. At the time, the publications that Graham was supplying images for did not have the capability to print in colour and they needed photographs in black and white. Being an early adopter of new technology, when colour was introduced, Graham would take an extra camera loaded with colour slide film to take an additional set of photographs, before colour photographs became the mainstay. The challenges with shooting using colour slide film was that it required a camera with proper exposure controls and an understanding of the environment to accurately capture the image. As Graham recalls “I had two cameras where I could swap lenses around. So, I could have a colour camera on my left shoulder, for example, and a black and white camera on my right shoulder, you had to remember which was your colour camera as they were identical.”

Despite shooting primarily in black and white, Graham noted “I realized, when I did take colour pictures, how beautiful it was to see something in colour and the earlier that I switched to colour, even just for myself, I would have colour images of races in the early 1980s, which turned out to be quite important.”

Processing the images

In the late 1970s, Graham would have to wait until the films were developed to see how successful the images he captured were, explaining “I would get them developed as and when I could, often working through the night to select several sets of images of a race and then courier them to London or New York or Brussels, wherever my clients were based.”

The extent publishers went to, to get Graham’s photographs were incredible. Talking about the 1987 Tour de France, Graham explained that “My undeveloped slide-film went on Concorde, each and every day for three weeks, they’d first go to Paris with the daily dispatch of drug-tests, post and other items flown by the Tour’s private plane. A local courier then picked up my package and put it on the morning’s flight to end up at the Sports Illustrated offices. They ended up using just six images of the entire race.”

Entering the digital age

As digital cameras evolved, from the mid-1990’s, Graham began to run a parallel set-up in the early-2000’s, realising he’d have to switch formats eventually. He used a film camera on one shoulder and digital on the other. He even travelled to the bigger races with a mobile slide-film processor, so as to make sure he kept pace with his all-digital colleagues. The digital pictures went out as web-size images to the websites that had emerged on the young and developing internet. A few hours later, the film-based pictures were developed, then digitally scanned and these quality images went to the magazines and commercial clients.

Graham remembers that “the quality of the equipment and the digital files were so poor. The images were good enough to be used in a newspaper. But if you put them in a cycling magazine, for example, and tried to put them across two pages, you couldn’t. The quality was so bad.”

The digital age

In 2003, Graham went 100% digital, realising that the digital file had finally reached the same level of quality as film. Then a new world of 3G technology evolved which posed a new challenge. As Graham explains: “There was now a race to get your images out before anyone else, it was the most important aspect of your day. The big agencies such as Reuters, Agence France-Presse (AFP) and the Associated Press (AP) each had a car travelling 15-minutes ahead of the Tour, inside was a driver with a technician in the back-seat, with a computer connected to a satellite dish on the roof of the car. The agency photographer would take his photographs from the motorbike and whenever they had something worthwhile, would accelerate up to the car and hand over their memory cards before dropping back to the race with a fresh set. This was very humbling and I had no chance against such a formidable foe.”

Eventually, around 2010, with the launch of the new Apple iPad, Graham was able to compete on an equal footing. Whenever he had a worthwhile shot, he would attach a cable between the iPad and camera and download the image he wanted to send. He would then do a colour check and edit it down in size by using an appropriate application. “Then it was just a question of finding a 3G signal, which was often only to be found in big cities. I remember Mark Cavendish winning a stage of the Tour that year. It was in a big city and the 3G was superb, and I’d got my editing technique spot-on, e-mailing an image to Cycling Weekly even before the podium ceremony had begun. They were astonished!”

By the time of Graham’s last Tour in 2016 technology had evolved and connectivity was rarely a problem. This meant Graham could use the latest Nikon technology and transmit images directly from the camera, immediately after some exciting cycling action such as a a crash or attack, or if the Tour had found some spectacular scenery. This evolution was noted by Graham, “I used to make black and white prints on the go, back in the early 1980s, and had followed all the innovations in photography since then, however I never imagined I would one day transmit my images out of the camera and halve my eternal post-race work in the press room.” Technology enabled Graham time, post-race, to find an open restaurant and enjoy an evening meal and some great wine when in France.

Reflections

Graham has been at the forefront of the cycling photography evolution but preferred taking pictures using film, but only for nostalgic reasons. “Every picture you take with a film camera, you have to do manual focus. You have to get your composition spot on. You have to get your exposure all calculated before you can take a picture. And now with digital cameras, even back in the early 2000s, that was all done for you.”

However, Graham certainly appreciates the new digital cameras, admiring their qualities “I got to realize how these beautiful new cameras can do so much more for you beyond anything film could ever do.”

Graham noted that one of the big advantages of the digital camera is that it is an instant picture. “That in itself opened up a lot of commercial interest and outlet for my pictures because I could do it so quickly. What it enabled me to do professionally is unbelievable.”

Art of photography evolved

The onset of digital photography changed the art of taking a photograph. “The digital camera helps you because you haven’t got to think so much. Instead of concentrating on the focus and exposure and everything else, you actually are concentrating on the subject of your next image. When you’re shooting film, you’re so limited, it’s pure photography.”

The digital camera resulted in new styles, as Graham recalls

“It forced me to actually look at a digital camera and see what I could do with it, which settings could I change to make things more exciting. It was a technology change, but also a kind of realisation that you could do an awful lot more with a camera when it was digital instead of film. It was an evolution of the art form.”

Impact to work

The introduction of digital cameras meant Graham’s workday changed. Working digitally meant that once the racing had finished and the images had been processed post-race, the job was complete. Conversely, shooting with film meant that many hours were required to process the film. Graham recalls “It never really ended, it just ran into another day, scrambling sometimes to finish the work post-breakfast before another stage!”

Working with film meant that images had to be couriered to agencies across the world where there was the risk of the slides being lost. In contrast with digital files, they can be easily backed up and less likely to be lost, especially as they fit onto a portable hard drive which could be more easily transported. Graham recounts one story.

“There was a race up in Leeds. And I was going up there with a cyclist called Tony Doyle, he was world pursuit champion. We were both going to meet a Publisher afterwards who was going to do a book about Tony Doyle with my pictures. The same publisher was already doing a book with Sean Kelly with my pictures and we decided that we’d go to Leeds where the Publisher was based. Tony would do the race. I would go up there in his car with all his bikes on the roof and all the sponsor signs on the car with my entire Sean Kelly collection. And we turned in the race. I took pictures.

And then we went to have dinner with the Publisher. And we made the big mistake of leaving Tony’s bikes on the car and all his kit. But also, me leaving all my pictures of Sean Kelly inside the car. And you know what happened? The whole lot got stolen. It took years to rebuild a catalogue of photographs of Sean Kelly.”

Conclusion

Photography has evolved in terms of technology and processes. Keeping pace with this evolution was Graham. Despite being an independent photographer, he was able to work alongside the large agencies, capturing key moments in cycling’s history. When we see an image in a magazine, I think we are guilty of not fully appreciating the commitment and expertise that has gone into capturing that shot. Now after speaking with Graham, I have a new appreciation of the challenges and work that goes into getting these images.